Diagnosis of heart failure

This resource has been initiated and supported by Roche Diagnostics Limited, who have had the opportunity to review it for factual accuracy but have had no input into its content. The resource was developed by Practice Nurse.

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure is the leading cause of hospitalisations in the over 65s and has a high prevalence in patients attending for regular review of long term illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD). General practice nurses play a vital role in the management of patients with long term conditions, and are therefore in an ideal position to identify the early signs and symptoms of heart failure in patients that are most at risk of developing this condition.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this resource, you will have a better understanding of:

- The need for prompt diagnosis of patients with suspected heart failure

- Risk factors for heart failure, and signs and symptoms that should prompt further investigation

- The role of NT-proBNP testing in investigating a potential diagnosis of heart failure

- NICE recommendations for action on the results of NT-proBNP testing

PRACTICE NURSE FEATURED ARTICLES

Alliance for Heart Failure. Diagnosing and monitoring heart failure. Practice Nurse 2022;52(6):22-23 https://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=2352

hFRenDs (specialist nurses in heart failure, renal disease and diabetes): A deep dive into heart failure. Practice Nurse 2022;52(7): online only https://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=2370

Bostock B. Heart failure: grasping the reins. Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):16-20 https://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=2265

25in25 initiative aims to reduce heart failure deaths. Practice Nurse 2023;53(01): online only. https://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=2393

This resource is provided at an intermediate level. Read the article and answer the self-assessment questions, and reflect on what you have learned.

Complete the resource to obtain a certificate to include in your revalidation portfolio. You should record the time spent on this resource in your CPD log.

Job code: MC-IE-02357

Date of preparation: September 2023

Contents

Diagnosis of heart failure

It is estimated that 920,000 people in the UK are living with heart failure, and with an ageing population and increased survival from acute cardiac events, such as myocardial infarction, the burden of heart failure in the UK is set to increase.1,2

More than 162,500 people currently wait 6 weeks or more for echocardiography, used to confirm a diagnosis of heart failure.3 Despite 40% of patients having symptoms that should have triggered an earlier assessment, 80% are initially diagnosed after a hospital admission.4 When patients are diagnosed with heart failure in an acute setting, rather than in the community, they are more likely to have worse outcomes and higher mortality rates.5

Heart failure can be challenging to diagnose: symptoms are non-specific and variable, can be confused with those of other conditions especially respiratory disease, and patients with heart failure often have one or more other comorbidities.

A systematic review found misdiagnosis of heart failure ranged from 16% in the hospital setting to 69% in general practice, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) the most common misdiagnosis.6 In a survey of 625 patients with heart failure, the most common initial misdiagnoses were asthma (25%), anxiety or depression (21%) and gastro oesophageal reflux disorder (19%).7

Heart failure prevalence increases with age. While the average age of a UK patient with heart failure is 75, for patients from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds, this drops to 69. For patient with heart failure in the most socioeconomically deprived areas, the average age of onset is early 60s.1

However, it can also affect patients at an earlier age, particularly after a cardiovascular event such as myocardial infarction, or conditions affecting the heart valves.1

WHEN TO SUSPECT HEART FAILURE

Symptoms of heart failure may develop gradually, over weeks or months or suddenly. As 98% of patients with heart failure have at least one other long term condition, such as type 2 diabetes or COPD,1 general practice nurses (GPNs) may be among the first healthcare professionals to learn about symptoms that may indicate the development of heart failure.

RISK FACTORS FOR HEART FAILURE8

- Coronary artery disease, including previous history of myocardial infarction

- Hypertension

- Atrial fibrillation

- Diabetes – people with type 2 diabetes have at least twice the risk of developing heart failure as people without9

- Family history of heart failure or sudden cardiac death (under 40 years)

TYPICAL SYMPTOMS8

- Breathlessness on exertion, at rest, on lying flat (orthopnoea) or on waking from sleep

- Fatigue and/or reduced exercise tolerance

- Oedema, particularly of the feet and ankles, as a result of fluid retention

- Palpitations, syncope

- Persistent cough (often productive of frothy sputum)

It is easy to assume that new symptoms are related to a pre-existing condition. Ask the patient:

- Have you noticed that you get more out of breath recently?

- Do you find you get more tired/exhausted with less effort?

- Do your shoes and socks feel tighter than usual, or leave marks?

- Have you put on weight recently? (May indicate fluid retention)

- Have you noticed a rapid, fluttering or pounding heartbeat?

- Have you been coughing much? Do you cough up frothy phlegm?

- How many pillows do you sleep on?

In addition to taking a careful and detailed history, a clinical examination should include:10

- Tachycardia (heart rate over 100 beats per minute) and pulse rhythm

- Laterally displaced apex beat, heart murmurs, third or fourth heart sounds (gallop rhythm)

- Hypertension

- Raised jugular venous pressure

- Respiratory signs such as tachypnoea, basal crepitations and pleural effusions

- Oedema

WHEN HEART FAILURE IS SUSPECTED

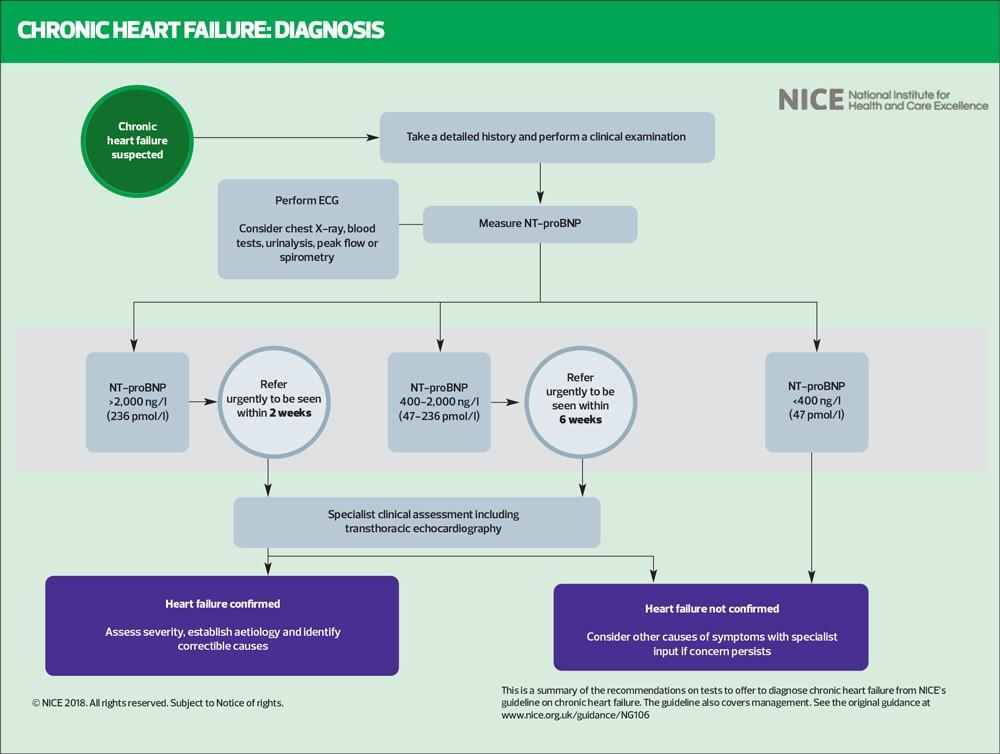

A preliminary investigation when a diagnosis of heart failure is suspected is the N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) blood test. These peptides are elevated in heart failure: very high levels are associated with a poor prognosis.10

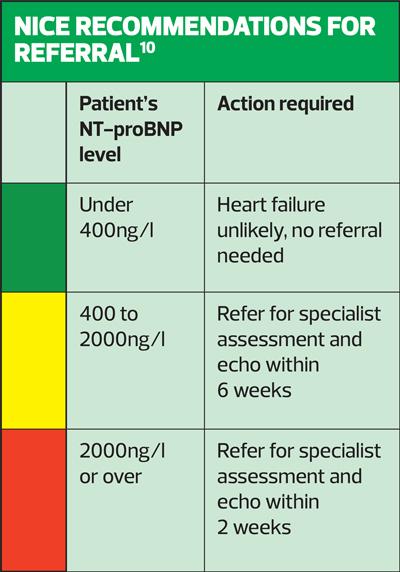

NICE recommends that people with suspected heart failure and an NT-proBNP level above 2,000 ng/l should be referred urgently (within 2 weeks) for specialist assessment and echocardiography.10 An NT-proBNP level less than 400ng/l makes a diagnosis of heart failure less likely. Natriuretic peptides may aid in establishing a working diagnosis in patients in whom heart failure is suspected, but echocardiography is required to confirm a diagnosis of heart failure.11

However, NICE warns that natriuretic peptide levels may be lower in individuals:10

- With obesity, African or African-Caribbean family background, or

- Receiving treatment with diuretics, angiotensin (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs)

Levels may be higher in individuals with chronic kidney disease or atrial fibrillation.10

NT-proBNP has better diagnostic accuracy than signs and symptoms alone.12 The test is widely available in primary care, and although NICE guidance recommending its use has been in place for over a decade,10 it has not yet been universally adopted.1

The NICE Quality Standard on chronic heart failure in adults, updated in January 2023, includes the use of NT-proBNP testing as a priority area for improvement.13 NT-proBNP measurement in primary care can indicate whether or not heart failure is likely when it is suspected (and there is no existing diagnosis of heart failure – it should not be used in patients who are already diagnosed.) People can then be referred appropriately for specialist assessment and echocardiography, begin appropriate treatment at an early stage, and reduce their risk of hospitalisation and mortality.13

An NT-proBNP level below the NICE cut-off point of 400ng/l can be used to rule out heart failure: consider other causes of symptoms, referring for specialist assessment if concerns persist.10

Job code: MC-IE-02357

Date of preparation: September 2023

References

1. British Heart Foundation. Heart failure: a blueprint for change; 2020. https://www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/health-intelligence/heart-failure-a-blueprint-for-change.pdf

2. Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet 2018;391:10120

3. NHS England. Diagnostic waiting times and activity data: May 2023 monthly report; July 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/07/DWTA-Report-May-2023.pdf

4. Bottle A, Kim D, Aylin P, et al. Routes to diagnosis of heart failure: observational study using linked data in England. Heart 2018;104(7):600-605.

5. BHF analysis of Lawson CA, et al. 20-year trends in cause-specific heart failure outcomes by sex, socioeconomic status, and place of diagnosis: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health 2019;4(8):e406-e420

6. Wong CW, Tafuro J, Azam Z, et al. Misdiagnosis of heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. J Card Fail 2021;27(9):925-933

7. Censuswide, Data from survey of 625 heart failure patients analysed for this report (Roche, Pumping Marvellous. Heart failure: the hidden costs of late diagnosis; August 2020). Data on file, Roche Diagnostics.

8. NICE CKS. Heart failure – chronic. When to suspect; last revised July 2023. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/heart-failure-chronic/diagnosis/when-to-suspect/

9. Kenny HC, Abel ED, Heart failure in type 2 diabets: Impact of glucose-lowering agents, heart failure therapies, and novel therapeutic strategies. Circulation Research 2019;124:121-141

10. NICE NG106. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

11. Modin D, Andersen DM, Biering-Sorensen T. Echo and heart failure: when do people need an echo, and when do they need natriuretic peptides. Echo Res Pract 2018;5(2):R65-R79

12. Wright SP, Dought RN, Pearl A, et al. Plasma amino-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide and accuracy of heart failure diagnosis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(10):1793-1800

13. NICE QS9. Chronic heart failure in adults: quality standard; 2011, updated January 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs9

Related modules

View all Modules