Renal considerations in patients with type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Renal impairment frequently co-exists with diabetes (type 1 and type 2).1 As many agents used to control blood glucose are metabolised by the kidneys, reduced renal function has important implications for the choice and dose of oral hypoglycaemic agents.

This module aims to raise awareness of how chronic kidney disease (CKD) impacts on the management of hyperglycaemia, including the need for dose reduction for many agents used in the management of type 2 diabetes.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this module, you will:

- Be familiar with the risk of declining renal function over time in patients with type 2 diabetes

- Be able to identify the factors that lead to the development of diabetic kidney disease

- Understand how to diagnose renal impairment and stage CKD

- Be aware of how CKD impacts on the management of hyperglycaemia, including the need for dose reduction for many agents used in the management of type 2 diabetes

This module is one of a series of five. Others in the series are:

- Targets for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes

- Tailoring therapy to the individual patient

- Short-term complications of type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular considerations in patients with type 2 diabetes

This resource is provided at an intermediate level. Read the article and answer the self-assessment questions, and reflect on what you have learned.

Complete the resource to obtain a certificate to include in your revalidation portfolio. You should record the time spent on this resource in your CPD log.

References

1. NICE NG203. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/ng203

Contents

Type 2 diabetes and renal function

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD*), also known as diabetic nephropathy, is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the UK.2 It affects people with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.2 Renal function may decline over time, and without appropriate intervention, can lead to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).3 More than 10,000 people in the UK have ESRD resulting from their diabetes, and people with diabetes are five times more likely to need renal replacement therapy (RRT).3 These patients, especially those with type 2 diabetes, are at significant cardiovascular risk.2

The pathological changes of DKD result from a combination of hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia and hypertension – both systemic hypertension and raised arterial pressure within the kidney itself (glomerular hypertension).4

These factors are also known to increase cardiovascular risk and indeed other aspects of cardiovascular disease (CVD) pathophysiology are thought to influence the development of DKD.5 This means that when someone with diabetes is diagnosed with CKD, the aim should be to delay progression and improve both renal and cardiovascular outcomes.

If recognised early, DKD in patients with type 2 diabetes can be treated: tight control of both blood glucose levels and blood pressure significantly reduces progression of DKD. Treatment of DKD reduces cardiovascular complications as well as kidney failure.6

*Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) or diabetic nephropathy refers to CKD caused by diabetes

Diagnosing CKD and DKD

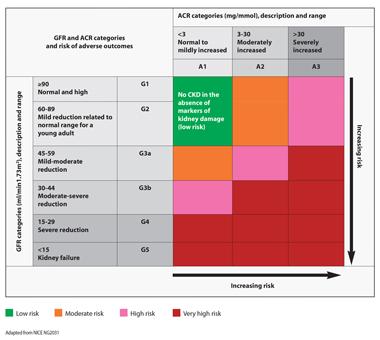

The diagnosis of renal impairment is made on the basis of abnormal blood and/or urine tests. A blood test is used to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and this, along with a urine test that measures the albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) can help to identify people with or at risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined as a reduction in kidney function or structural damage (or both) present for more than 3 months, with associated health implications.7

Care should be taken to repeat abnormal tests in order to ensure that any change is sustained and not transitory, and to identify the presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), which will require more urgent intervention.2 If a reduced eGFR (less than 60ml/min/1.73m²) has been recorded for the first time, a repeat test should be carried out within 2 weeks to exclude AKI. To determine the rate of progression of renal impairment, an abnormal eGFR should be recorded at least three times over a period of 90 days.1

The risk of adverse outcomes increases with increasing ACR and decreasing GFR (Figure 1).1

Adapted from NICE NG203.1

The impact of renal impairment on managing blood glucose

In 2022, NICE updated its guideline on the management of type 2 diabetes and currently recommends the use of metformin* first line.

Patients should be assessed to determine if they have chronic heart failure (CHF) or established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or are at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease. In patients with CHF or established ASCVD, an SGLT2 inhibitor with proven cardiovascular benefits should be offered in addition to metformin. In patients who are or become at high risk of developing CVD, an SGLT2 inhibitor with proven cardiovascular benefits should be considered in addition to metformin.8 In people not at high CVD risk, NICE’s current guideline recommends the addition of a DPP-4 inhibitor, pioglitazone, a sulfonylurea or SGLT2 inhibitor if monotherapy has not controlled HbA1c to below the patient's agreed threshold.8 If a combination of two drugs does not achieve adequate blood glucose control then a third agent or insulin-based treatment should be started.8

In patients with reduced renal function, a DPP-4 inhibitor that does not require dose adjustment at any level of renal impairment, (e.g. linagliptin) would be appropriate.9 Linagliptin is also the only DPP-4 inhibitor to have its renal safety profile confirmed (as a pre-specified secondary outcome) vs placebo in the CARMELINA cardiovascular outcomes trial (CVOT), in which 74% of patients had pre-existing CKD.10

Renal impairment will have a significant impact on the choice of hypoglycaemic agent, so it is important to check for warnings and dose adjustment recommendations based on renal function in the SmPC for each drug before prescribing.

*In patients with type 2 diabetes and impaired renal function, the dose of metformin may need to be adjusted. It should be reviewed if the eGFR falls below 45ml/min/1.73 m2, and metformin should be discontinued if eGFR is below 30ml/min/1.73 m2.11,12

Hypertension and CKD

Hypertension can worsen CKD and vice versa so it is important to treat blood pressure effectively. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are known to have a positive effect on the kidneys and offer renoprotection so these are often the first choice therapy when treating people who have hypertension, diabetes and CKD.12

NICE CKD guidelines1 state that unless contraindicated, an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) should be offered to all people with CKD and diabetes who have an ACR of 3 mg/mmol or more (ACR category A2 or A3) and/or those who have hypertension and an ACR of 30 mg/mmol or more (ACR category A3).

The dose of medication may need to be adjusted (up or down) depending on the stage of CKD and/or HbA1c.

However, many people will need more than one antihypertensive drug to get their blood pressure to target so the combination of an ACE inhibitor or ARB (A) with a calcium channel blocker (C) or thiazide-like diuretic (D) should be added to get the patient to target (130/80mmHg in people with diabetes and kidney disease).14

Lifestyle interventions are always the key to reducing CVD risk, both in the general population as well as those people who have diabetes, so advice and support should be offered on the benefits of weight management, healthy eating, an active lifestyle and avoiding smoking.15

In the self-assessment that follows, hypothetical case scenarios based on fictitious patients with type 2 diabetes are presented. Please refer to the relevant Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing any of the medications mentioned.

References

1. NICE NG203. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/ng203

2. Min TZ, Stephens MW, Kumar P, Chudleigh RA. Renal complications of diabetes. British Medical Bulletin 2012;104:113-127

3. Diabetes UK. Us, diabetes and a lot of facts and stats. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/statistics

4. Marshall SM. Natural history and clinical characteristics of CKD in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014;21(3):267-72.

5. Cheng H, Harris RC. Renal endothelial dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 2014;14(1):22-33.

6. Diabetes UK. Preventing kidney failure in people with diabetes: Position statement; August 2016. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/specialist-care-for-children-and-adults-and-complications/preventing-kidney-failure-in-people-with-diabetes

7. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Chronic kidney disease, 2022. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chronic-kidney-disease/

8. NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2015 (2022 update). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

9. Trajenta (linagliptin) Summary of Product Characteristics. SmPCs available at EMC: www.medicines.org.uk (GB) and https://www.emcmedicines.com/en-GB/northernireland/ (NI)

10. Rosenstock J, Perkovic V, Johansen OE, et al. Effect of linagliptin vs placebo on major cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular and renal risk. JAMA 2019;321(1):69-79

11. Glucophage (metformin) Summary of Product Characteristics. SmPCs available at EMC: www.medicines.org.uk (GB) and https://www.emcmedicines.com/en-GB/northernireland/ (NI)

12. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin F, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669-2701

13. HOPE Study Investigators. Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Lancet 2000;355:253-59

14. NICE NG136. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management, 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

15. NICE CG181 Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification, 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181

Related modules

View all Modules