Reducing cardiovascular risk: latest recommendations

Mandy Galloway

Mandy Galloway

Editor, Practice Nurse

Practice Nurse 2024;54(2):12-15

Many patients who might benefit significantly from lipid-lowering therapy are not being treated at all, so the latest NICE guideline aims to increase the numbers of patients who are offered a statin to reduce their risk of cardiovascular events

As Practice Nurse pointed out in our last issue, it is worth reading the latest NICE guideline on Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification,1 as much of the work of general practice nurses will involve cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, by supporting lifestyle changes, prescribing, titrating and monitoring lipid-lowering medication.

The guideline is an update of previous guidance on the topic, and includes new and updated recommendations – among others – on initial lipid measurement and referral for specialist review; discussions and assessment before starting statins; new targets for secondary prevention; and new advice on what lipid-lowering treatments should be used – or not used – routinely.

But before any treatment starts, patients should be identified using a systematic strategy to identify people who are likely to be at risk of CVD, rather than opportunistic assessment, and their risk assessed.1

ASSESSING RISK

NICE recommends using QRISK3 to assess the 10-year risk of an individual without established CVD having a CVD event.1 It is expected that – because it includes additional fields, such as severe mental illness, regular corticosteroid use and atypical antipsychotic use – it will perform better than QRISK2 at predicting CVD events in patients with these risk factors.

However, QRISK3 may still underestimate the risk of CVD in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychoses, so it is important that clinical judgement is used when interpreting the results of the assessment.

This is important because severe mental illness (SMI) affects 5% of the population,2 and people with SMI have a significantly shorter life expectancy than the general population, with cardiovascular disease the most common cause of death after suicide.3

However, not all practices have QRISK3 integrated into electronic clinical systems yet, so GPNs may still have to use QRISK2 while waiting for an update – but should use the online version of the later version (https://qrisk.org) when assessing CVD risk of people taking corticosteroids or atypical antipsychotics.

Other groups in whom CVD risk tools may underestimate risk include:

- People treated for HIV

- People already taking medication to treat CVD risk factors

- People who have recently stopped smoking

- People taking drugs that can cause dyslipidaemia, such as immunosuppressant drugs

- People with autoimmune disorders and other systemic inflammatory disorders

People aged 85 or older should be considered to be at increased risk of CVD because of age alone, more so if they also smoke or have raised blood pressure.

Communicating results

Allow enough time in the consultation to provide information on the risk assessment and to answer your patient’s questions – arrange a follow up consultation if needed.

For people whose risk score is less than 10%, and for people under the age of 40 who have CVD risk factors, consider using a lifetime risk tool, such as QRISK3-lifetime (https://qrisk.org/lifetime/).

Lipid measurement

As in previous guidelines, NICE recommends measuring both total blood cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein to achieve the best estimate of CVD risk. However, healthcare professionals should use clinical findings, a full lipid profiles and family history to judge the likelihood of a familial lipid disorder, rather than using strict cut-off values alone.

BASELINE TESTS

Before starting statins, perform baseline tests and clinical assessment, including all of the following:

- Smoking status

- Alcohol consumption

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Full lipid profile

- Diabetes status

- Renal function

- Transaminase level (alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase)

- Thyroid stimulating hormone level in people with symptoms of under- or over-active thyroid

There is no need to exclude statin treatment in people who have raised transaminase levels but which are less than 3 times the upper limit of normal.

Discuss whether or not the patient has ever had persistent generalised unexplained muscle pain or weakness, and if they have, measure creatinine kinase levels. If creatinine kinase levels are:

- More than 5 times the upper limit of normal, re-measure after 7 days; if still 5 times the upper level of normal, do not start statin treatment.

- Raised but less than 5 times the upper limit of normal, start statin treatment at a lower dose.

However, NICE reminds clinicians that statins are contraindicated in pregnancy because of the risk to the unborn child of exposure to statins. Statins should be stopped if there is a possibility the patient is pregnant, and 3 months before attempting to conceive, and not restarted until after breastfeeding has ceased.

INITIATING A STATIN

Decisions about starting statin therapy should be taken after an informed discussion between the clinician and patient about the benefits and risks of statins. Clinicians should take into account potential benefits of lifestyle changes, the individual’s preferences, the presence of any comorbidities, whether they are on multiple medications, whether or not they are frail and their life expectancy.

A common perception among patients is that statins cause muscle aches and pains – however, the risk of muscle pain, tenderness or weakness associated with statin use is small, and the rate of severe muscle adverse effects (rhabdomyolysis) because of the statins is extremely low.

Patients should be advised to always consult the patient information leaflet, a pharmacist or prescriber for advice when starting other drugs or thinking about taking supplements. This is because of potential interactions between statins and other medications and some food stuffs, e.g. grapefruit juice.

There is no need for a complete ban on grapefruit juice if the patient is taking – or is to be started on – atorvastatin, but grapefruit juice does potentiate the efficacy of some statins, such as simvastatin or lovastatin. Some authors now say the increased risk of rhabdomylolysis is minimal compared with the greater effect in preventing heart disease, and that grapefruit juice should not, therefore, be contraindicated.4

Before starting statins, treat comorbidities and secondary causes of dyslipidaemia, and discuss the benefits of lifestyles changes – recognising that people may need help to modify their lifestyle.

Recommend that people at high risk of CVD should aim for a diet in which total fat intake is 30% or less of total energy intake, saturated fats less than 7% of total energy intake, and that where possible saturated fats are replaced by mono-unsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Advise these patients to do aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities5 – and where people are unable to do moderate intensity physical activity, to exercise at their maximum safe capacity.

STATINS FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION OF CVD

NICE has set a target of a greater than 40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol for primary prevention, although some authorities argue that this may not enough to reduce risk in those at the highest risk of CVD.6

To achieve this, NICE recommends atorvastatin 20mg for those who have a 10-year QRISK3 score of >10% – and also to those with a less than 10% QRISK3 score if there is a possibility that their risk may be underestimated, or if the person wants to start statin therapy. Treatment should not be withheld from people aged 85 and older, but prescribers should be aware that the presence of comorbidities, multiple medications, frailty and lower life expectancy may alter the balance of risk and benefits.

The Guideline Development Committee (GDC) decided to keep the starting dose at 20mg for all patients starting atorvastatin for primary prevention, because although they recognised that higher doses have a greater effect, starting at a lower dose was likely to be preferred by patients; however, clinicians should consider up-titration as appropriate.

STATINS FOR SECONDARY PREVENTION OF CVD

Controversially, NICE has recommended a target of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels of 2.0 mmol/l or less, or non-HDL cholesterol levels of 2.6 mmol/l for secondary prevention in people with established CVD.

This target has also been recommended as an indicator for the Quality and Outcomes Framework in place of the current target for LDL-C below 1.8 mmol/l.

The NICE targets are also higher than those recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), both of which recommend LDL-C targets of below 1.8 mmol/l and ideally below 1.4 mmol/l.7,8 The NHS lipid lowering pathways also recommend an LDL cholesterol below <1.8 mmol/l.

It is worth noting that the GDC agreed that LDL-C and non-HDL cholesterol levels should be reduced as much as possible in people with CVD, but stated that it was ‘not cost effective to offer the full range of treatments to everyone with CVD.’

Initial treatment

NICE therefore recommends atorvastatin 80mg as initial treatment for people with established CVD, whatever their cholesterol level, with a lower dose if:

- It could react with other drugs

- There is a high risk of adverse effects

- The individual would prefer a lower dose.

Measure liver transaminase (ALT) and full lipid profile 2–3 months after starting (or changing) lipid-lowering treatment, and measure ALT again at 12 months. There is no need to repeat this test again unless clinically indicated.

Treatment escalation

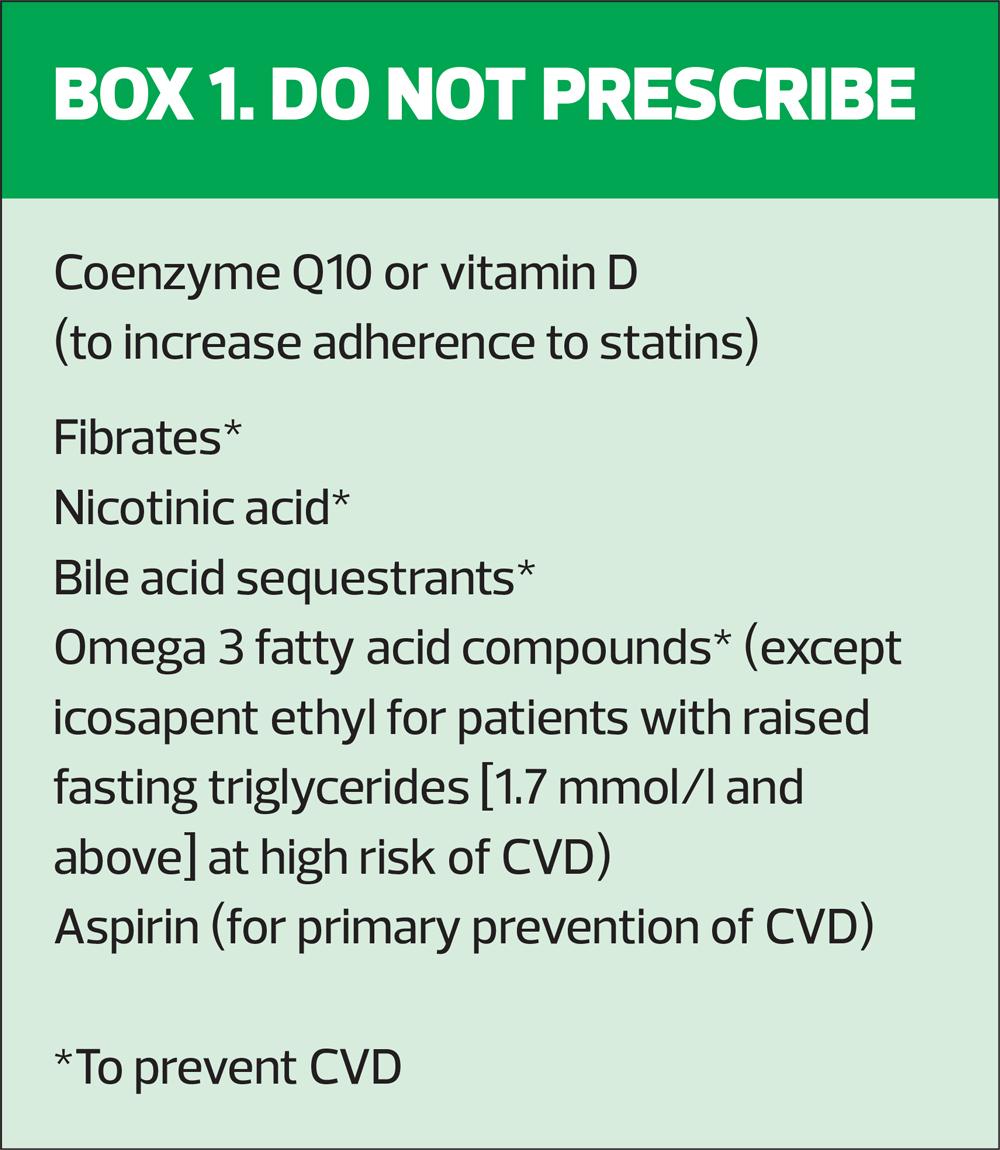

For people on the maximum tolerated dose and intensity of statin who do not reach target lipid levels, prescribers should consider additional lipid-lowering medications.

- Alirocumab, a PCSK9 inhibitor, is recommended only if LDL-C is persistently above 4.0 mmol/l for people (with existing CVD) at high risk of CVD, and 3.5 mmol/l in people at very high risk.* Alirocumab is not recommended for primary prevention, but may be used in people with familial hypercholesterolemia with LDL-levels above 3.5 mmol/l.9

- Evolocumab, also a PCSK9 inhibitor, is recommended only if LDL-C is persistently above 4.0 mmol/l for people (with existing CVD) at high risk of CVD, and 3.5 mmol/l in people at very high risk.* Evolocumab is not recommended for primary prevention, but may be used in people with familial hypercholesterolemia with LDL-levels above 5.0 mmol/l.10

- Ezetimibe is recommended for adults who cannot tolerate statin therapy, and also for people on an appropriate dose of statin who do not achieve target total or LDL-C levels.11

- Inclisiran is only recommended for secondary prevention in people at high risk* or who have LDL-C levels persistently above 2.6 mmol/l despite maximum tolerated lipid-lowering therapy (statins with or without other lipid-lowering drugs, or other lipid-lowering therapies when statins are not tolerated or contraindicated).12

*High risk is defined as history of acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction or unstable angina requiring hospitalisation), coronary or other arterial revascularisation, coronary heart disease, ischaemic stroke, peripheral arterial disease. Very high risk is defined as recurrent CV events or polyvascular disease.

The GDC said all four of these medications were found to produce clinically significant reductions in LDL-C and non-HDL-C levels in clinical trials (most subjects were also taking a statin), and resulted in modest reductions in major CVD events such as myocardial infarction, stroke and related deaths.

But the committee added that escalation of treatment was only cost-effective for people on statins with LDL-C levels of more than 2.2 mmol/l. There was a little more uncertainty about cost-effectiveness of escalating treatment for people with LDL-C levels between 2.0 mmol/l and 2.2 mmol/l, but that an LDL cholesterol target of 1.8 mmol/l was not cost-effective.

Where the target is based on non-HDL-C levels, the target is 2.6 mmol/l, which the GDC recognises as being ‘slightly higher’ than other national and international targets because, unlike other targets, both targets are based on the cost-effectiveness of treatment escalation.

OPTIMISING STATIN TREATMENT

Don’t forget that if patients are not meeting their lipid targets – whether for primary or secondary prevention – it is worth addressing adherence, and the timing of their statin dose. Encourage them to continue to make improvements to their diet and lifestyle, and to make further changes if needed.

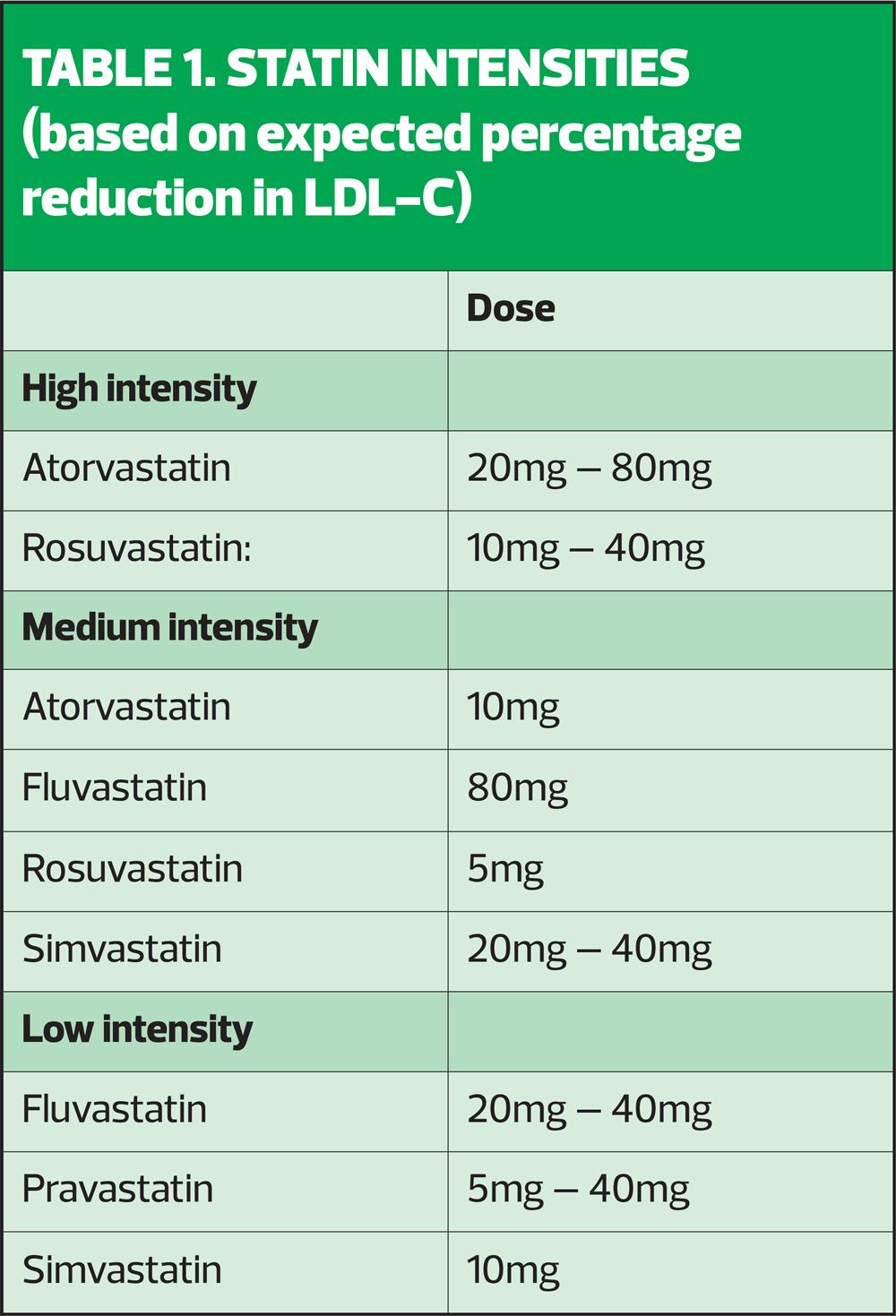

Consider increasing the statin intensity or dose (see Table 1) if the individual is not already taking a high-intensity statin at the maximum tolerated dose.

If the individual reports adverse effects when taking a high-intensity statin, discuss the following options:

- Stopping the statin and trying again when symptoms have resolved to see if their symptoms are related to the statin

- Changing to a different statin in the same intensity group

- Reducing the dose

- Changing to a lower-intensity statin

While ideally, the patient should receive the recommended dose of a high-intensity statin, if they cannot tolerate it, aim to treat at the maximum intensity and dose that they can tolerate – remember, any statin at any dose reduces CVD risk.

As with management of any other long term condition, patients on lipid-lowering treatment should have an annual review, which provides opportunities to discuss adherence, lifestyle, and to address other CVD risk factors.

CONCLUSION

Most of the recommendations in the latest guidance about statin treatment for primary prevention of CVD remain unchanged from the 2014 update of the guideline, but national audit data suggest that only about half of people with a QRISK score of 10% or more are on lipid-lowering treatment.

Similarly, the specific target for secondary prevention is close to that already used as part of QOF for 2023/24 – but for the majority of patients, the target is not being met – in fact, in June 2023, the CVDPREVENT audit reported that only 28.7% of patients were meeting the target.

While counsel of perfection suggests that the targets are sometimes clumsy and probably not low enough, the fact remains that many patients who might benefit significantly from lipid-lowering are not being treated at all, to any target, and those who are being treated are still not meeting targets.

So, if this guideline is followed, more patients will receive lipid-lowering treatments – statins, ezetimibe and others. This will increase medication and monitoring costs to the NHS, and inevitably, contribute to increased workload in general practice. But the upside is that increased treatment can be expected to lead to a reduction in CVD events for our at-risk patients.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG238. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification; December 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238

2. NHS England. NHS England pledge to help patients with serious mental illness; 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2014/01/mental-illness/

3. Taylor J, Shiers D. Don’t just screen – intervene. Protecting the cardiometabolic health of people with severe mental illness. J Diabetes Nursing 2016;20:297-302. https://diabetesonthenet.com/journal-diabetes-nursing/dont-just-screen-intervene-protecting-the-cardiometabolic-health-of-people-with-severe-mental-illness/

4. Lee JW, Morrris JK, Wald NJ. Grapefruit juice and statins. Am J Med 2016;129(1):26-29. https://www.amjmed.com/article/s0002-9343(15)00774-3/fulltext

5. Bostock B. New lipid targets at odds with international standards. Practice Nurse 2024;54(2):7

6. Department of Health and Social Care. Chief Medical Officers’ Physical activity guidelines; 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/physical-activity-guidelines

7. European Society for Cardiology (ESC) 2019 Guidelines on Dyslipidaemias (Management of); August 2019. https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Dyslipidaemias-Management-of

8. American Heart Association (AHA) 2023 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease; 20 July 2023 https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168

9. NICE TA393. Alirocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia; 2016 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta393

10. NICE TA394. Evolocumab for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta394

11. NICE TA385. Ezetimibe for treating primary heterozygous-familial and non-familial hypercholesterolaemia; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta385

12. NICE TA733. Inclisiran for treating primary hypercholesterolaemia or mixed dyslipidaemia; 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta733

13. NHS Benchmarking Network. CVDPREVENT; March 2023. https://www.nhsbenchmarking.nhs.uk/news/cvdprevent-third-annual-audit-report-now-published

Related articles

View all Articles