Treating heart failure in primary care

LOUISE CLAYTON

LOUISE CLAYTON

Advanced Nurse Practitioner,

University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, Co-chair Alliance for Heart Failure

Practice Nurse 2022;52(8):8-9

In the third and final part of this series of articles on heart failure, we will look at how to treat newly diagnosed patients as well as help manage the illness in those already diagnosed with heart failure

The Alliance for Heart Failure has written this series of articles as a ‘call to action’ because general practice nurses have a vital role to play in ensuring we manage the ever-growing burden of heart failure. In the first part, we looked at recognising symptoms and what to do next,1 in the second we wrote about diagnosis using the appropriate pathways.2 By the end of this article, we want practice nurses to feel confident in knowing they can make an important difference to the lives of people living with heart failure.

STARTING TREATMENT IN PRIMARY CARE

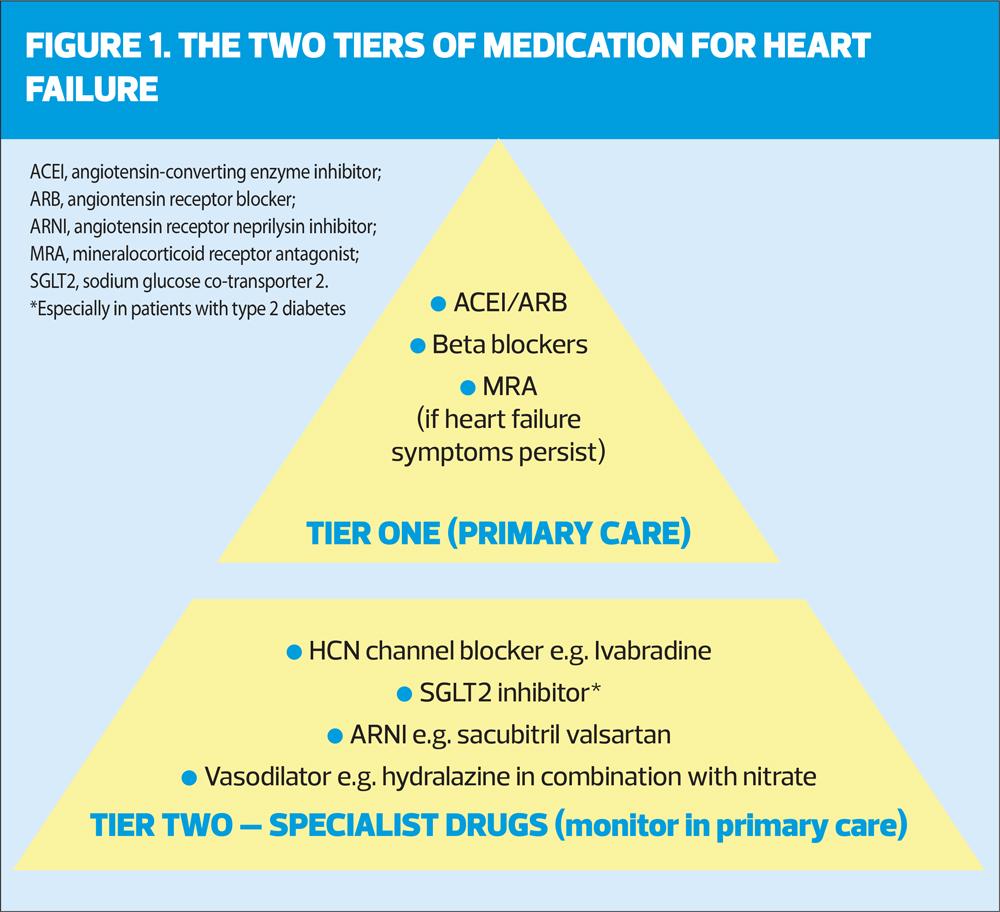

Once a diagnosis of heart failure has been confirmed, initial treatment can start straight away in primary care while a patient waits to see a specialist. There are two types of heart failure, chronic and acute, and the medication used to treat heart failure can be separated into two tiers (Figure 1).

ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) and beta blockers are the first, ‘Tier One’, treatments for a person with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). ACEIs work by relaxing the blood vessels and reducing blood pressure while beta blockers prevent the heart from beating too quickly.

Both these medications are included on the QOF indicator for heart failure and can be started in primary care before a patient sees a specialist. You should be able to access local guidelines on how to use these treatments. Generally a ‘start low, go slow’ approach should be adopted by non-specialists (See titrating drugs below). Monitoring of blood pressure, pulse, and kidney function at a maximum of two weeks after starting new drugs is essential.3

For patients whose symptoms persist despite maximum tolerated doses of ACEI or ARB plus a beta blocker, consider adding a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA).3

Once a patient has been seen by a specialist, additional ‘Tier Two’ drugs may be initiated (Figure 1).

It is important for practice nurses to familiarise themselves with Tier Two drugs. It’s common for patients on these specialist drugs not to receive optimal doses. In primary care, there is the opportunity to increase the doses to provide better response.

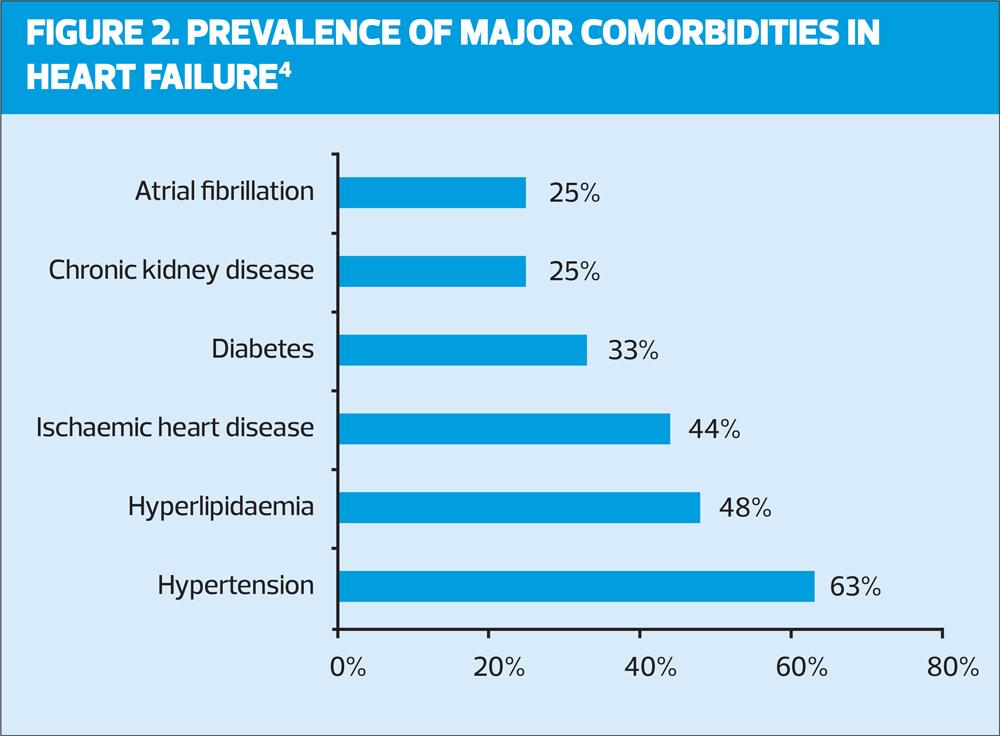

Be on the look out for worsening or persistent symptoms in heart failure patients during their check ups, particularly in those with comorbidities (see Figure 2).4

Being able to spot a patient who is not receiving all of the ‘big four’ drugs – ACEI/ARB or ARNI, beta blocker, MRA, and an SGLT2 inhibitor – or who is on a suboptimal dose, could save a life. Liaise with a GP or heart failure specialist if you have a concern.

TITRATING DRUGS FOR MAXIMUM EFFICIENCY

NICE guidelines state you should start Tier One drugs at a low dose and titrate upwards every two weeks, until the maximum tolerated dose is reached.3

A key QOF performance indicator is making sure that a patient has reached their maximally tolerated dose for heart failure medication within 12 months of their diagnosis.5

You should measure serum sodium and potassium and assess renal function and blood pressure before starting treatment and after each upward titration.

Guidelines for maximum dosage should be available locally. If not, discuss with your GP or local specialist.

CARE PLANS, CARDIAC REHABILITATION AND CRT

Every heart failure patient should receive a care plan.6 If the opportunity arises, you should check in with them to see they are following their plan and making the best use of available services.

Cardiac rehabilitation services should also be available in your local area. Making the patient aware of these and ensuring they understand the importance of attending regularly is key to managing their condition long term.

Alongside this, therapies such as Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy (CRT) can play a vital role in helping patients, particularly those with moderate to severe heart failure, to manage their symptoms. CRT is a pacemaker that emits tiny pulses of electricity to help resynchronise the heart. Up to 70% of appropriately selected heart failure patients can benefit from this treatment.7

We hope these series of articles on treating heart failure will help you make a difference to the lives of patients. If you have any questions, or would like to know more about the work we do at the Alliance for Heart Failure, you can visit www.allianceforheartfailure.org

REFERENCES

1. Alliance for Heart Failure. Diagnosing and monitoring heart failure. Practice Nurse 2022;52(6):22-23

2. Clayton L. Diagnosis heart failure using the correct pathway. Practice Nurse 2022;52(7):22-23

3. NICE NG106. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

4. Khan MS, Tahhan AS, Vaduganathan M, et al. Trends in prevalence of comorbidities in heart failure clinical trials. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22(6):1032-42

5. NHS England. Update on Quality Outcomes Framework changes for 2022/23; March 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/update-on-quality-outcomes-framework-changes-for-2022-23/

6. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 European Society for Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599-3726

7. Chinitz JS, d’Avila A, Goldman M, et al. Cardiac resynchronisation therapy: who benefits? Ann Glob Health 2014;80(1):61-8

Related articles

View all Articles