When guidelines collide - Part two: Asthma treatment

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK-COX

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK-COX

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery Moreton in Marsh

Education Lead Education for Health Warwick

The three main asthma guidelines for the UK contain conflicting recommendations, but there is also common ground. Familiarity with the key points will help you 'pick and mix' to suit the individual patient

In last month’s article, we focused on the different approaches that guidelines take to the diagnosis of asthma.1 This month, we sum up the way in which the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN),2 NICE,3 and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines4 complement or conflict with each other in terms of the management of asthma. This article will consider the management of asthma from childhood to adulthood and will consider the risks and benefits of following one guideline or another. The article focuses on the overarching principles of the guidelines but detailed information relating to the rationale for the approach taken in each publication can be found by reading them all in full.After reading this article, you should:

- Be prepared to implement the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) code of conduct when supporting people with their asthma management

- Recognise that BTS/SIGN, NICE and GINA all have different approaches to the management of asthma

- Be aware of the difference between their approaches

- Consider the importance of personalising care to the individual being treated for asthma, using the most relevant guideline

The essence of the NMC code of conduct can be summed up by the ‘4 Ps’:

Prioritise people

Practise effectively

Preserve safety

Promote professionalism and trust

This code can and should be implemented when caring for people with asthma and should also be used as a reflective tool. In each consultation, nurses should ask themselves how well they adhered to the 4 Ps. When it comes to dealing with asthma, this can be an effective way of monitoring the way in which people are supported to treat and self-manage this condition. Of the three main guidelines mentioned above, each contains recommendations which are potentially more patient-focused for a specific individual than others so general practice nurses (GPNs) who treat people with asthma should be aware of the common ground, agreed by all three guidelines and also know when they diverge and why so that they can ensure that the best approach is taken for that individual. The key is to ensure each patient gets personalised, effective and safe care delivered by a trustworthy healthcare professional (HCP).

BTS/SIGN – ASTHMA MANAGEMENT IN CHILDREN AND ADULTS

BTS/SIGN provides guidance for children (aged up to 12 years) and separate recommendations for adults that apply to anyone over the age of 12. The treatment escalator is available in the full guideline on p78-79. No step up should be initiated without assessing adherence, inhaler technique and possible new triggers or co-morbidities first. Treatment is usually tried for at least 6 weeks before the impact is fully evaluated and a step up is contemplated, but treatment should also be started at the level appropriate for the severity of the asthma. Use of reliever therapy can also be a guide to the need to step up, with BTS/SIGN saying that using a reliever three times a week is an indication to step up.

Under 5s

A summary of the steps is as follows:

- Consider a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) first line and continue if there is a good response

- Add in/replace LTRA with a very low dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) – e.g. 100mcg bd of a standard ICS such as beclometasone (Clenil).

- Move up to a low dose combination inhaler (ICS with a long acting beta2 agonist (LABA) e.g. Seretide 50mcg 2 puffs bd)

- If there is an inadequate response to treatment with a low dose ICS/LABA and an LTRA, referral is recommended and the combination inhaler can potentially be increased up to a medium dose.

At all stages, a short acting beta2 agonist (SABA) should be available in a metered dose inhaler (MDI) with spacer for symptom relief.

5-11-year age group

The suggested steps are:

- Start with a very low dose ICS (100mcg bd of a standard ICS such as beclometasone or 50mcg bd of fluticasone propionate (Flixotide) as before

- Add a LABA in a combination inhaler

- Increase the dose of the ICS to a medium dose ICS/LABA

At any point a trial of an LTRA, for 4-6 weeks, can be attempted. A response can be expected within a few days of starting this treatment.

Consider referral where high dose ICS/ LABAs, theophyllines or oral corticosteroids may be initiated.

Age 12 and older

From age 12, the adult guidelines come into force and these recommend the following strategy:

- Start with a low dose ICS (200mcg standard ICS bd)

- Step up to a low dose combination (approximately 400mcg total daily dose of standard ICS equivalent)

- Step up to a medium dose combination (approximately 800mcg total daily dose of standard ICS equivalent)

- Consider adding in other therapies

(e.g. LTRA, a long acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA] i.e. Spiriva Respimat) where appropriate

Examples of treatment strategies for age 4

- Start with Monelukast 4mg daily

- Add Clenil 50mcg 2 puffs bd via pMDI and spacer

- Move to Seretide 50mcg 2 puffs bd via pMDI and spacer (this is only combination licensed for this age group and it is only licensed to give at 2 puffs bd)

- Consider referral at any stage but certainly if good control is not achieved on these therapies

Examples of treatment strategy for age 5–11

- Start with Clenil 50mcg 2 puffs bd or Flixotide 50mcg 1 puff bd

- Move up to a low dose combination inhaler (Symbicort 100/6mcg licensed from age 6 if patient is able to use the Turbohaler or Seretide 50mcg 2 puffs bd)

- Consider adding in Montelukast 4–5mg daily (4mg from age 6 months to 5 years, 5mg age 6–14 years) and/or Spiriva Respimat 2 puffs daily (now licensed from age 6)

- At this point or at any stage before this, consider referral.

Interestingly, 1 puff bd of Symbicort 100/6mcg would give an ideal total daily dose of 200mcg ICS but the licensed dose for age 6 and over is 2 puffs bd, whereas the licensed dose for adolescents and adults age 12 and over is 1–2 puffs bd. HCPs should use their clinical judgement in deciding the most appropriate approach.

Examples of treatment strategy for age 12–18

- Start with a low dose ICS e.g. Clenil 100mcg 2 puffs bd or Flixotide 50mcg 2 puffs bd

- Move up to a licensed combination inhaler for this age group e.g. Flutiform 50mcg 2 puffs bd, Symbicort 100/6mcg 2 puffs bd. Relvar is also licensed in this age group.

- Increase up to a medium dose combination inhaler e.g. Flutiform 125mcg 2 puffs bd, Symbicort 200/6mcg 2 puffs bd.

- Add in Montelukast 5-10mg (10mg from age 14) and/or Spiriva Respimat

- Consider referral at any stage if response to treatment is poor

Example of treatment strategy for age 18+

- Clenil 200mcg bd

- Fostair 100/6mcg 1 puff bd

- Fostair 100/6mcg 2 puffs bd.

- Add Montelukast 10mg or Spiriva 2.5mcg 2 puffs od

- Refer

Treatment decisions should be based on age, patient’s ability to use the device, patient preference. So where a pMDI and DPI are both available these elements should be used as a guide. All patients should have a pMDI and spacer with salbutamol for use in an emergency and the type of device should be maintained, if possible, for all treatments, preventer and reliever. There is some debate in the respiratory community as to whether people using the ‘one inhaler’ maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) approach should still be given a pMDI and spacer for acute exacerbations. For those using a pMDI, a spacer has usually been recommended, especially in children, the elderly and those who are less dexterous or who find it difficult to co-ordinate and/or inspire in a slow, steady, deep breath. However, for routine use other devices are available to guide inspiratory flow rates, such as the Flo Tone device. This device connects to the pMDI and is small, portable and available on prescription. The tone is activated if the patient is breathing in at the correct speed to optimise deposition of the medication.

Put succinctly, then, BTS/SIGN guidelines suggest the following approach:

- Low dose ICS (very low dose in the under 12s)

- Low dose combination

- Medium dose combination

- LTRA/LAMA/ theophylline

NICE – ASTHMA MANAGEMENT IN CHILDREN AND ADULTS

As mentioned in the previous article,1 NICE has a unique element to its guidelines in that it includes a health economic evaluation. This element can lead to NICE making recommendations which differ from other guidelines where there is little or no difference between two interventions, but one is cheaper. This is one of the main reasons why NICE treatment guidelines look very different from BTS/SIGN. NICE guidelines in general have been criticised for putting economics before pragmatism.6 In an initial draft guideline for diabetes, for example, cheap medication which needed to be taken with every meal, was given priority over other more established drugs which could be prescribed once daily, ignoring the fact that adherence would be poorer and so glycaemic control would be harder to achieve. NICE was strongly criticised for this and amended the guidance accordingly. In the asthma guidelines there were similar concerns, but these were not amended as a result. So, this is what NICE recommends for the management of asthma in children and adults.

In the under 5s

- Offer a SABA.

- Consider ICS for symptoms at presentation that clearly indicate the need for maintenance therapy (for example, asthma-related symptoms three times a week or more, or causing waking at night) or suspected asthma that is uncontrolled with a SABA alone.

There was considerable disappointment when this guidance was published as it appears to return to the old ‘step’ one which was to use a SABA alone. It had been argued for years that asthma is an inflammatory condition and as such, an ICS would be needed to control inflammation. NICE seems to have returned to the idea that a SABA might be used first, especially with that last comment that an ICS can be initiated if symptoms are not ‘controlled’ with a SABA. Of course, bronchodilators only relieve symptoms, they do not control the inflammation so this wording could be misleading, especially for clinicians who are less familiar with the importance of addressing inflammation in asthma. The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD)7 highlighted the fact that most people who died from asthma actually had mild or moderate asthma, were overusing their blue inhaler and were on no ICS or were on inadequate doses.

NICE then goes on to say that if an ICS is initiated and an improvement in symptoms is seen it should be stopped after 8 weeks. As studies suggest that inflammation can take as long as 9 months to stabilise this seems to be a strange suggestion, not least to the parents of the child who is now well, playing happily without coughing or wheezing and sleeping through the night! The idea is that any improvement is shown to be the result of treatment, and not just a coincidence. NICE states:

- If symptoms resolved on ICS then reoccurred within 4 weeks of stopping, restart the ICS at a paediatric low dose

- If symptoms resolved on ICS but reoccurred beyond 4 weeks after stopping, repeat the 8-week trial of ICS at a paediatric moderate dose

Once the child is established on ICS therapy, the first recommended step up, is to

- Add an LTRA as second line therapy

This approach is an option in the BTS/SIGN guidelines but as seen above, BTS/SIGN recommends an ICS first and an LTRA as an add-in.

The next age group NICE addresses is children age 5-16. This age group overlaps the older children’s guidance (age 5–11) and the adult guidance (age 12 and over) from BTS/SIGN. For children age 5–16 NICE recommends a similar approach to the one taken with those age under 5:

Offer a paediatric low dose of an ICS for children and young people aged 5 to 16 with:

- Symptoms at presentation that need maintenance therapy (e.g. asthma-related symptoms three times a week or more, or causing waking at night) or

- Asthma that is uncontrolled with a SABA alone

Once again, this seems to endorse the use of reliever therapy alone up to three times a week before an ICS is deemed necessary, which is at odds with BTS/SIGN. It could also be argued that this has a flavour of ‘let’s try to do without inhaled steroids if possible’ which is at odds with BTS/SIGN’s enthusiasm for ICS in any case of suspected or confirmed asthma.

As the next steps, these are the recommendations from NICE:

- Add LTRA as second line therapy. If the patient’s symptoms are not controlled after a trial of treatment

- Stop LTRA and add a LABA. If symptoms are not fully controlled on an ICS/LABA

- Use MART approach

- Not controlled? Use moderate dose ICS/LABA – at a fixed dose or using the MART approach then

- Consider referral and use of high dose ICS/LABA and/or theophylline

There are some concerns when taking this approach. In adolescents, LTRAs may not offer any advantages over increasing the dose of ICS,8 or introducing a LABA9 and using an ICS/LABA may be more pragmatic than a tablet and an inhaler, where there may be a risk of people taking the tablet but omitting the inhaler – a concern previously noted with ICS inhalers and LABAs being given separately.10 Chopping and changing treatment options may lead to a loss of confidence in the healthcare professional from the child and/or parents. Also, MART therapy is only licensed from age 12 and even then only with one product, Symbicort 100/6mcg. This can be given as 1 puff bd or 2 puffs once daily, either morning or evening, with additional puffs to relieve symptoms up to a maximum of 12 puffs a day,11 but this regimen still requires the child to be able to use a Turbohaler. Symbicort does come in a pMDI but this is only licensed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Adults are deemed to be age 17 and above in the NICE guidelines but clinicians should be aware that not all inhalers are licensed to use in 17-year olds. Combination inhalers that are only licensed from age 18 include Fostair, Duoresp and Fobumix.

In adults, NICE recommendations for treatment are similar to the 5-16 year old algorithm with appropriate dose adjustments. The suggested steps are:

- Start with a low (adult) dose ICS

- ICS plus LTRA

- ICS plus LABA +/- LTRA

- MART regimen

- Higher dose ICS

GINA – ASTHMA MANAGEMENT IN CHILDREN AND ADULTS

Unlike the BTS/SIGN and NICE guidance, GINA guidelines are international guidelines. They offer advice on the management of asthma in children age 5 and under, children aged 6-11 years and people aged 12 and over.

For the 5 and under age group, GINA suggests that an ICS should be used in those with frequent viral-induced wheezing and those who suffer from interval asthma symptoms. Initially, they state, a trial of regular low-dose ICS should be carried out but then as-needed or episodic ICS may be considered. They base this suggestion on evidence that reductions in asthma exacerbations seems to be similar when ICS are used regularly at low doses or intermittently with high dose ICS.12

GINA also states that LTRAs can be used first line.

When stepping up treatment in the under 5s, GINA suggests moving to a medium dose ICS by doubling the low dose option, although a low-dose ICS with an LTRA is another option, echoing BTS/SIGN. Recommended low doses in this age group are:

- Beclometasone 50mcg bd e.g. Clenil

- Fluticasone propionate 50mcg bd e.g. Flixotide

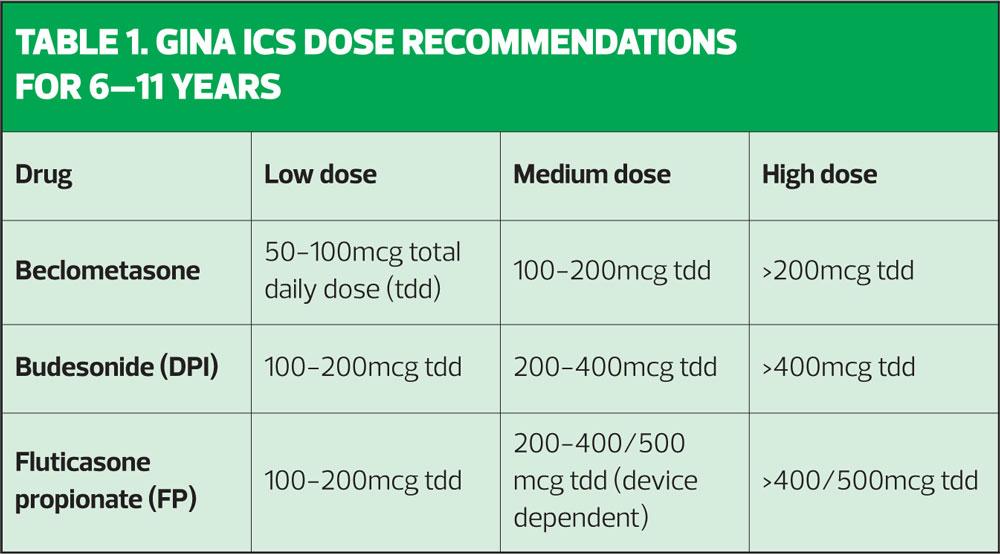

6–11 age group

GINA recommends:

- A low dose ICS, then

- A medium dose ICS

- A LABA may then be added

GINA recommends the use of a medium dose ICS in children age 6–11 in preference to an ICS/LABA although it says the impact of both options on asthma control is the same. On that basis, it might seem preferable to spare the dose of ICS by adding a LABA instead, but GINA still opts for a higher dose ICS. In the GINA guidelines, suggestions are given for low medium and high dose options, which are not dose equivalent but which reflect the different products and devices available.

The doses in Table 1 (overleaf) are slightly different from those suggested by BTS/SIGN, mainly because they are not advising on dose equivalence but are suggesting pragmatic dosing for the products currently available. These are just examples and other ICS molecules are included in the table in the full guidelines (p45). GINA also states that high dose ICS should be used in children who are waking weekly with asthma symptoms. GINA guidelines state that dose adjustments, both up and down, can be made at around 2–3 months.

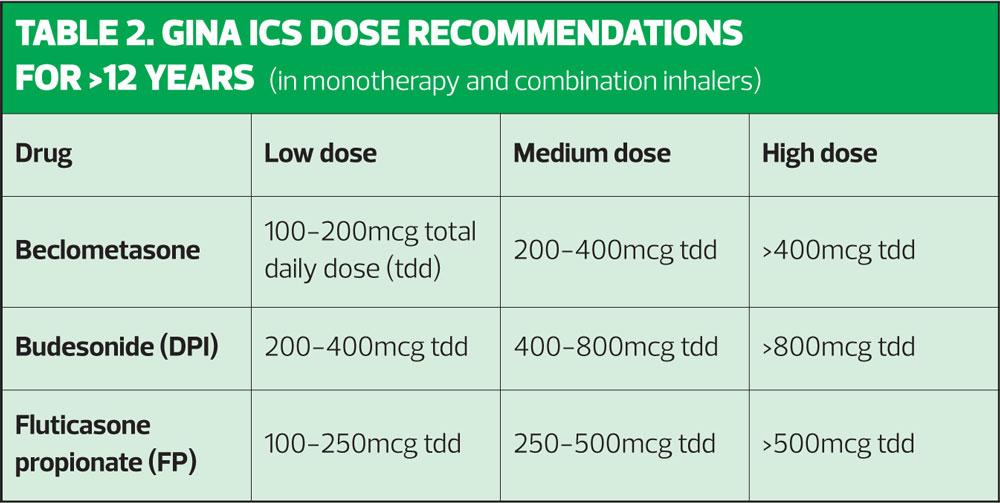

Adults

GINA recommends the following:

- Low dose ICS with SABA prn

- Low dose ICS/LABA plus prn SABA or MART

- Low dose ICS/LABA as MART or medium fixed dose ICS/LABA

- Consider adding in a long acting antimuscarinic (LAMA) (tiotropium)

(age 12 and above)

- Consider referral

- High dose ICS/LABA has less evidence of benefit and has a less favourable risk: benefit ratio than lower doses

The guidelines also say that LTRAs and theophyllines are alternative options throughout, depending on the individual patient.

GINA argues the case for not initiating an ICS in the following situations:

- SABA use/symptoms no more than twice a month

- No night waking in the past month

- No risk factors for acute exacerbations including no exacerbations in the past year

- Normal lung function (FEV1 >80% predicted)

However, the guidelines also state that stopping an ICS is not recommended, unless this is being used to confirm the diagnosis and the impact of the ICS, as mentioned by NICE.

CONCLUSION

In summary, both BTS/SIGN and GINA agree that ICS therapies should be used in asthma management. GINA states: ‘Treatment with ICS at low doses reduces asthma symptoms, increases lung function, improves quality of life, and reduces the risk of exacerbations and asthma-related hospitalizations or death’ (p46). NICE may seem to suggest that SABAs might be an initial option but is clear that when symptoms are frequent, ICS should be initiated. BTS/SIGN and GINA both recommend using low dose ICS/LABAs as the first step up in the over 12s although GINA advises the use of a medium dose ICS (see Table 1) before using a combination in children age 6-11 years. It is important to remember that the BTS/SIGN and GINA definitions of low, medium and high doses are not interchangeable. BTS/SIGN and GINA see LTRAs as an optional add in therapy, whereas NICE places them as a second line therapy, primarily on the basis of cost. GINA and NICE both recommend using MART regimens as a way of improving control when a fixed dose regimen does not control symptoms effectively. All three guidelines recommend reviewing and confirming the diagnosis, addressing adherence, identifying and managing co-morbidities and triggers before stepping up. Treatment should always be stepped down once control has been maintained for at least 3 months, although GINA and BTS/SIGN are keen that ICS treatment is maintained and not stopped in most cases.

For the GPN working at the coal face, the difference between guidelines can seem confusing and overwhelming. However, the reality is that these guidelines offer different ways to treat patients, based on their individual presentations, needs and preferences and that is something to be celebrated.

REFERENCES

1. Bostock-Cox B. When guidelines collide – part one: asthma diagnosis. Practice Nurse 2018;48(6):22–24. http://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=1703

2. BTS/SIGN (2016) British guideline on the management of asthma https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/

3. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management, 2017 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

4. Global Initiative for Asthma. GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2018. https://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/

5. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code, 2015 https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

6. Price C. Are NICE guidelines becoming a ‘laughing stock’? Pulse Online, 2015. http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical/prescribing/are-nice-guidelines-becoming-a-laughing-stock/20009342.article

7. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: The National Review of Asthma Deaths, 2014 https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills

8. Chauhan BF, Jeyaraman MM, Singh Mann A, et al. Is adding an anti-leukotriene to an inhaled corticosteroid better than using an inhaled corticosteroid alone for persistent asthma? Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017;3:CS010347 http://www.cochrane.org/CD010347/AIRWAYS_adding-anti-leukotriene-inhaled-corticosteroid-better-using-inhaled-corticosteroid-alone-persistent

9. Chauhan BF, Ducharme FM. Effects of long-acting beta2-agonists compared with anti-leukotrienes when added to inhaled corticosteroids. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014;1:CD003137 http://www.cochrane.org/CD003137/AIRWAYS_effects-of-long-acting-beta2-agonists-compared-with-anti-leukotrienes-when-added-to-inhaled-corticosteroids

10. Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (2014) Asthma Long-acting ß2 agonists: use and safety https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/asthma-long-acting-ss2-agonists-use-and-safety/asthma-long-acting-ss2-agonists-use-and-safety

11. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Symbicort 100/6mcg summary of product characteristics, 2017 https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1326/smpc

12.Kaiser SV, Huynh T, Bacharier LB, et al Preventing exacerbations in preschoolers with recurrent wheeze: A meta- analysis. Pediatrics 2016;137(6): e20154496 http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/137/6/e20154496.long

Related articles

View all Articles